Death, Bowling With Pigeons and Exploding Furniture

During the afterparty for the opening of Alucine’s Space Invaders group exhibition at Gallery 1313, Jorge Lozano, the artistic director of Alucine mentioned to me that children had reacted positively to my piece. I found his comment surprising, since the piece consists of an altar to revolution and death via Jackie Chan’s The Protector, surrounded by a bloodbath of gutted teddy bears with their faces removed and substituted by the visages of Mexican cadavers. We chatted about how great the show looks, and the caliber of the works presented, and the fact that the show is comprised of an international selection of artists: Taiwanese, Argentinean, Salvadoran, Canadian, Mexican and Colombian, (not to mention the hundreds of film and video works from artists spanning the globe that were being shown in several locations around the city). Jorge also mentioned a recent headline about the festival that read: “WHERE ARE ALL THE LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS IN THE ALUCINE FESTIVAL?” I found this question to be very compelling. Yes, where were the Latin American artists? And just what is a “Latin American artist” anyway?

I mentioned the headline to Guillermina Buzio, the festival coordinator for Alucine, and she replied that “The question has some sense: What does it mean to be Latin? Latin Americans come from so many countries, with different musical styles, accents, socio-economic classes, cultural backgrounds, skin tones, and customs. For instance, I’m from Argentina, but my ancestors were German and Eastern European Jews, Hugo Ares (the coordinator of installations) on the other hand, is of purely Spanish background. Yet we are both Argentineans. We speak with the same accent, we both identify with the Tango. This is our background.”

Guillermina sees the role of festivals such as Alucine as a means of going beyond the stereotype of the salsa-dancing Latin Lover that is constantly portrayed in the media as the hallmark of Latino-ness. “People are confused about what a Latino is” says Guillermina. “Latinos are not a homogeneous group that can be easily packaged. Most Latin Americans are already several removes from a monolithic cultural identity as it is. As I said before, they have different cultures, mores and identities, and coming to a country like Canada highlights these differences.”

So, what is a “Latino Artist?” In my mind, the epitome of a Latin artist is an individual who, having been born to Latin American (or non-Latin for that matter) parents in any number nations, and possibly being black, white, Asian, Aboriginal, South Asian or any combination of the above, sets out to incorporate elements of their already hybridicized culture with elements of the culture of the country that they happen to inhabit at the moment, within a contemporary art context. In this sense, a Latino artist is no different from any other artist. The tendencies in their mode of creation are the same: They are critical of authority, obsessed with identity, or engaged with formal/art historical concerns. Their works are humorous or poignant, centered around specific geo-political issues, or reveling in their own aesthetic beauty. On the other hand, there is a tendency that can be said to be exclusively Expat Latin: The tendency to pine for the chimera of “The old country” whose harsh, cruel reality never matches the imagined or remembered idyllic landscapes in our mind.

During the late sixties and early seventies, the Tropicalistas (the Brazilian avant-garde movement headed by Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes and one of the greatest composers of the Twentieth Century, the iconoclast Tom Ze) put forth their theory of “Cultural Cannibalism”. Having been inundated with North American and European pop culture, the Tropicalistas decided to cannibalize these cultural elements, ingesting them, mixing them with Brazilian pop culture and folklore, and vomiting them back at the world. Although the movement was short lived (it was easily and irrevocably crushed by the political dictatorship at the time) the practice of Cultural Cannibalism went on to become the norm for Latin artists everywhere.

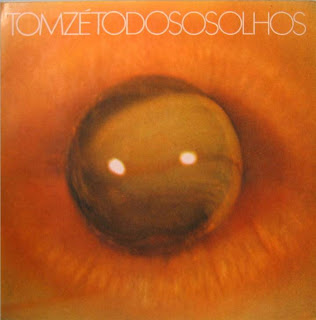

But what does a Taiwanese artist like Tsui Kuang-Yu have to do with Latin American art? The answer is, everything. Tsui’s work consists of a series of video vignettes in which the artist is portrayed in a number of ludicrous activities: Running on floating wooden planks in a flooded hallway, rolling bowling balls to scare pigeons, shooting golf balls at incoming traffic, to name a few. All of the above are performed in a perfectly deadpan way. These absurd acts lampoon the futility of contemporary life while taking a stance against conformity. Tsui’s anti-authoritarian stance is echoed in the work of Brazil’s Tom Ze, whose album Todos Os Olhos features a cover made up of a photograph of an eye-like marble inserted inside the artist’s anus. The album was released in 1973, at the height of the military dictatorship in Brazil, when censors would stop any art that was remotely rebellious and composers like Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were being imprisoned and exiled to Great Britain. This period in Brazilian history is reminiscent of the “White Terror” period in Taiwan (from May 19, 1949 to July 15, 1987) in which 140,000 Taiwanese suspected of opposing Chiang Kai-shek’s government were sent to prison or executed. During this time in Taiwan, criticism or discussion of the government and its actions were strictly prohibited under martial law. Ze’s album made it past the Brazilian government censors, as the cover with the anal marble resembled the eye of a lovely exotic bird, and the joke was on them.

When I ask Guillermina whether she prefers alternative spaces to galleries (in the past, Alucine has had art shows at Gallery 1313 and Shift Gallery, as well as in alternative spaces like the Portuguese/Latino bar Cervejaria Downtown) she tells me that both types of spaces are great depending on the nature of the installations. “As long as the pieces fit the space, there is no predilection. If you put something great and aesthetic in a non-gallery space, what matters is how you present the work.”

“The context of the gallery is definitely geared for shows, but it limits the audience. Having an art show at a bar limits the gallery audience, but it lends itself to art that is more about perception and less about the intellectual, and it makes the art more accessible to the general public. Art is an important means of expression and if you segregate it to intellectuals, then other people will be alienated and prevented from seeing it. Art cannot be intellectual. It must be done by perception and impression. It must be universal and community-based like radio and television.”

Guillermina’s populist attitude towards art exhibitions is another common trait among Latin American artists. Even though we come from so many different countries and cultures, we have a need to reach beyond our boundaries. Like a group of differing animals holding for dear life to a log that is floating inexorably towards the rapids, we become unlikely allies.

Audience participation is also the focus of Sofian Audry, Miriam Bessette and Jonathan Villeneuve’s whimsical piece entitled Trace. As I was installing my piece, Villeneuve was busy assembling a complex network of wires, lights, miniature speakers and motion sensors. He spoke in French with his colleagues over Ichat as he worked on his laptop. I asked Villeneuve how his piece was coming along, “it is finished”, he said. It looked like a spider’s web of wires and lights. “An interesting sculpture”, I thought. Then someone walked into the room and the whole thing came to life. The motion sensors activated the lights and speakers, creating an instant visual and aural portrait of myself. Brilliant! Trace was the only other piece besides mine that was object- based in a show consisting almost exclusively of video projections.

As I lit my piece with small intimate lamps so that they cast creepy shadows on the teddy bear corpses, a projection of two men talking filled the opposite wall. It was W. Mark Sutherland and Nobuo Kubota’s Slowpokes, in which the artists are shown in profile mouthing sound poetry to one another in slow motion. Their mouths emit absurd, slurred sounds, as they face off in a sort of Dadaist version of Dueling Banjos. The piece is humorous and raises the issue of the lack of connectedness in our society.

The title Space Invaders is highly charged. A play on the name of the popular seventies game whose object is to defend the earth by destroying the invading aliens by means of laser rays, it also refers to the general attitude in the United States towards Hispanic immigrants (legal or otherwise), and to the taking over of the gallery space by the installation works. Guillermina tells me that “with video installations you have to take over the space whether you are exhibiting in a bar or a gallery” and indeed, most works are about the occupation of space. The works are intimate, heartfelt and lyrical, whether they deal with physical space or emotional space.

Colombian artist Andres Garcia de la Rota is a case in point; his piece Campo Abierto - Campo Cerrado (Open Field – Closed Field) features two LCD video screens framed like paintings. One video shows a field as seen from the window of a poor field laborer’s house. The field is shown in a slow zoom spanning several minutes. The other video is also a zooming shot, but this time the field laborer’s house is the subject. It is seen as a white speck in the distance, and as the zoom progresses the house is magnified until it fills the picture plane. Both videos progress at a snail pace in a contemplative fashion so that we see two points of view unraveling simultaneously: Inside looking out and outside looking in. This piece begs a closer look at the merits of the ironic distance that has become the norm in today’s contemporary art.

An Ambitious Plan by Argentinean artist Eugenia Calvo, on the other hand, deals with the alteration of interiors. The installation consists of several single channel videos on monitors placed in close proximity to one another. Each video shows the artist as she barricades herself with furniture inside a house clearly belonging to a well-to-do family in Buenos Aires. The artist breaks up the space within the house by rearranging its furniture in unlikely ways, and finally by blowing up the furniture with explosives. Thus she deconstructs and violently alters our perception of her space, within the space of the gallery.

The show culminates with a work by Kika Nicolela entitled Face to Face, in which over twenty men and women are asked to respond, in camera, to five questions about love. “At times,” Kika tells me, “The responses are lively, and at times, the subject is silent, overcome by sadness, doubt, and sometimes the responses are cynical”. The sound is not synched to the image, so that the audio becomes contrapuntal to the slow motion footage of the subject’s facial expressions.

I ask Kika whether her piece deals with saudade (an exclusively Brazilian term for an emotional state combining longing, nostalgia, and loss) she replies that to a certain extent it does. She tells me that she made this piece as a response to what she was going through during her first marriage, and that listening to her subjects speak so candidly about their loves, frustrations and losses was therapeutic for her. When I ask her how her marriage turned out, she says that it’s a long, painful story, and that she will tell me all about it later on when we’re both drunk. Considering that we have known each other for a total of five minutes, this thought is comforting to me. Here’s an artist who is not afraid to be heartfelt, and who is not reluctant to lay her soul bare. And perhaps this is a more adequate stereotype of Latino-ness. It is certainly one that I can live with.

Labels: alucine, caetano veloso, darkness, gallery tpw, space invaders, tom ze, tropicalia, tropicalist, ulysses castellanos

<< Home